Young Muslims Mental Health

May 06 2020

Muslims throughout the UK and the rest of the world are currently observing the month of Ramadan, an opportunity for reflection and prayer. It is also a month of fasting, with Muslims not eating or drinking during daylight hours to demonstrate their devotion to Allah. Various studies have looked at the mental health impact of religiosity, and have identified that religious people are better able to cope with periods of stress and worry, and have a greater sense of purpose and meaning (Abu-Hilal, Al-Bahrani and Al-Zedjali, 2017; Dein, Cook and Koenig, 2012).

It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that during the current coronavirus pandemic, the overlap between the lockdown and Ramadan might be assumed to be a useful protective factor when it comes to the mental wellbeing of young Muslims. Is this the case?

In a previous role, I worked in Greater Manchester delivering the National Citizen Service programme for a diverse group of young people, and our week-long residential trip occurred during Ramadan. I observed first-hand the way in which fasting and prayer played an important role in the lives of the young Muslims in my group. I learned a great deal from this group of young people, and since that time I have worked with many young Muslims and had some fascinating conversations about mental health over the years. I am extremely aware of my status as a white male who holds no religious beliefs, and I am keen to establish that my intention is not to speak on behalf of young Muslims, but to try and provide helpful information and encourage further discussion and knowledge-sharing. Please accept my apologies for any errors in terminology or understanding – this article is written with positive intentions and goals at all times.

Just this month, a recent report has shown that the BAME community is being disproportionately affected by the coronavirus outbreak, due to factors including higher rates of certain ailments like diabetes, multiple generations living under the same roof, higher levels of poverty and for certain elements of the community, distrust of the authorities. Looking specifically at Muslim experiences of the COVID-19 outbreak, Islamic Relief UK have raised concerns about the huge financial impact of the lockdown upon UK Muslims. This is a particularly worrying time for many people, and there have been concerns raised by a number of mental health charities about the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of people affected. Worryingly, the Muslim Youth Helpline, a vital source of support for young Muslims in the UK, has highlighted that Muslims in the UK are less likely than other people to speak openly about mental health issues and to seek support.

It is an unfortunate fact that there remains a high level of stigma facing people experiencing mental health issues. For people in the Muslim community, they can often experience additional stigma from within the community. Studies have shown that some Muslim people believe that mental or physical illness is a sign of ‘distance’ from Allah, a punishment or an indication of a lack of faith (Ciftci, Jones and Corrigan, 2013), whilst others have highlighted that the concept of izzat, defined as self-respect and honour, can negatively affect young Muslim women’s wellbeing and their willingness to seek support (Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence, 2018).

Although the observances of Ramadan are often an extremely positive experience for young Muslims, there have been concerns raised about the physical and emotional impact on vulnerable young people. Fasting is compulsory for those not chronically ill, which culturally is often interpreted as physical illness rather than mental ill health. For young Muslims experiencing issues around eating disorders and mood disorders, Ramadan can be a particularly challenging time with eating and sleep habits interrupted and an expected focus on self-discipline. Combined with the additional pressures of being unable to meet friends, leave the confines of the house and concerns about the pandemic, it is clear to see that the mental health of young people within the Muslim community is currently a real area of concern

It is also an area for consideration that within the Islamic faith, the concept of kader, or destiny, is paramount. This can lead to a sense of acceptance that sickness is a sign of Allah’s will, which can lead to either a sense of fatalism or alternatively a belief that recovery is in the hands of Allah (Ciftci, Jones and Corrigan, 2013). Although I am in no way suggesting it is an article that accurately represents the views of all or even the majority of Muslim people, I recently read a piece on an Islamic website regarding the coronavirus which talked specifically about this concept, with the author suggesting that faith is more important than maintaining social distancing measures:

I ask: What is the most dangerous thing that one could possibly be doing during these plagued times? Is it to be on the receiving end of a sneeze, to not wash one’s hands after being in public, not being stocked up on food, or perhaps being in the middle of a congested gathering? In reality, it is none of these. The single most dangerous act that one could possibly do at this moment is continuing as usual in sinning.

For many young Muslims in the UK, the issue of acculturation can cause significant distress. Community and family expectations can come into conflict with western ‘norms’ when it comes to dress, behaviour and lifestyle. This can negatively affect young Muslims’ sense of identity, leading to emotional distress and confusion (Hutnik and Coran Street, 2010). Help seeking might be seen as un-Islamic within certain areas of the community, leading to potential isolation or damaged family ties. At the current time, when families are on lockdown together, this can be especially damaging.

However, it is also extremely important to acknowledge that there are significant benefits for young Muslims at this time of stress. In addition to the positive role of faith in maintaining good mental wellbeing, one of the key elements of Ramadan is the importance of looking out for one another. The itfar meal at sunset can be a wonderful opportunity for families to spend time together and zakat, the charitable donations required of those who are earning and have accumulated savings for more than a year as one of the Five Pillars of Islam are helping support vulnerable people during this difficult time.

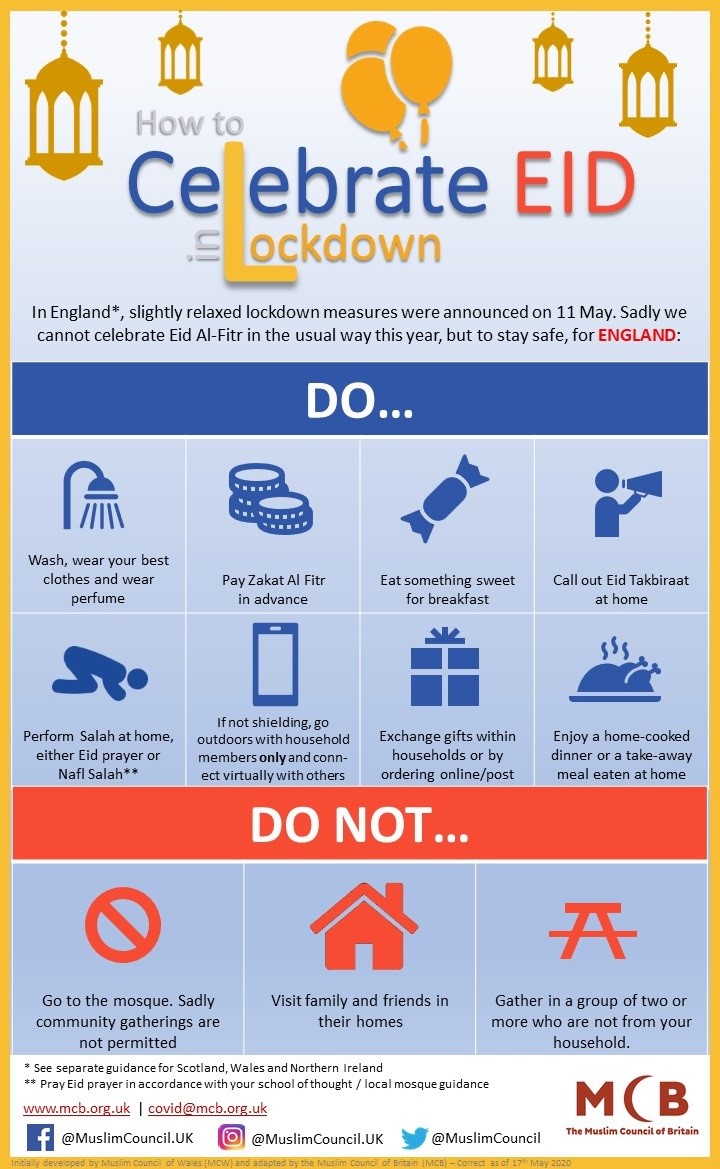

Positive steps are being taken to support young Muslims during this period of uncertainty and stress. The Muslim Council of Britain has released guidance to encourage people to keep safe, using the hashtag #RamadanAtHome to ensure adherence to government guidelines and religious observances. In addition, the Muslim Youth Helpline continues to play a vitally important role, offering faith and culturally sensitive support to young British Muslims.

The intention of this article is to highlight areas for consideration, and to encourage further dialogue on how best to move forward. In order to do this, we need to listen to those people within the Muslim community who are working to support the mental wellbeing of themselves and others, to offer culturally sensitive care and to be aware of our own privilege and preconceptions. This week is Mental Health Awareness Week, and the theme is ‘kindness’. We all need to work to develop kinder and more compassionate communities, taking into account one another’s circumstances and needs.

References

Ciftci, A., Jones, N. and Corrigan, P. (2013) ‘Mental Health Stigma in the Muslim Community’, Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 7(1)

Dein, S. and Cook, C. and Koenig, H. (2012) ‘Religion, Spirituality and Mental Health: Current Controversies and Future Discourse’, Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(10)

Gunashinghe, C., Hatch, S. and Lawrence, J. (2018) ‘Young Muslim Pakistani Women’s Lived Experience of Izzat, Mental Health, and Well-being, Qualitative Health Research

Hussain, S. The Independent (2020) ‘NHS officials told me Muslim households are particularly vulnerable to coronavirus – it’s important to understand why’

Hutnik, N. and Coran Street, R. (2010) ‘Profiles of British Muslim Identity: Adolescent Girls in Birmingham’, Journal of Adolescence

Islam21C (2020) ‘What COVID-19 has Uncovered’

Islamic Relief (2020) ‘Over Half of UK Muslims Will Struggle to Pay Bills During Coronavirus Crisis’

Muslim Council of Britain (2020) ‘Coronavirus Guidance for Mosques and Madrassas’

Muslim Youth Helpline. www.myh.org.uk

Nursing Times (2015) ‘Cultural competence in nursing Muslim patients’

The Cut (2016) ‘For Muslims With Eating Disorders, Ramadan Can Pose a Dangerous Choice’

Watts, M. (2020) ‘Report states BAME communities could be at greater COVID-19 risk’

Related

Popular

Upcoming event

Join us for the Bath Half Marathon to support young people and their mental health!

The Charlie Waller Trust

The Charlie Waller Trust is a registered charity in England and Wales 1109984. A company limited by guarantee. Registered company in England and Wales 5447902. Registered address: The Charlie Waller Trust, First Floor, 23 Kingfisher Court, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5SJ.

Copyright © 2025 The Charlie Waller Trust. All rights reserved.