What is children's behaviour telling us?

June 12 2023

The Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition (CYPMHC) brings together leading charities to campaign jointly on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people.

It’s a privilege to have been involved in this report. It breaks new ground on the subject of mental health and behaviour in schools and, I feel, addresses a pressing need.

Tough Times

Times are tough at the moment for a lot of people. Individuals, families and communities are facing challenges on many fronts: housing, the cost of living, healthcare delays – this list goes on.

Schools are, in many ways, a mirror of society and its challenges. They face extreme pressures, not just in preparing the adults of the future but often in addressing family issues and societal ills. They’re having to respond to rising mental health issues but without the budget or access to local specialist services or alternative forms of education for children that need them.

Rising suspensions

According to government statistics, suspensions have increased – there were 240 for every 10,000 pupils in the spring term of 2021/22. 43 percent of these were attributed to persistent disruptive behaviour. Rates of suspension and exclusion are higher for children eligible for free school meals. The highest rate of suspensions is among pupils with special educational needs; looking at ethnicity, Gypsy/Roma pupils have the highest rate. Children need education to fulfil their potential as a child and into adulthood. It can’t be right that the most vulnerable children in society are increasingly excluded from school, with evidence suggesting a clear path into the criminal justice system as a result, at significant personal and societal cost.

The highest rate of suspensions is among pupils with special educational needs.

Rates of suspension and exclusion are higher for children eligible for free school meals. The highest rate of suspensions is among pupils with special educational needs; looking at ethnicity, Gypsy/Roma pupils have the highest rate.

Is behaviour linked to mental health?

Is there a link between behaviour and mental health? A growing body of evidence suggests there is. For example, a report by Impact on Urban Health recognises that, during childhood and early adolescence, mental health problems can manifest as behavioural difficulties.

The Coalition’s report aims to explore the links and to look at how school behaviour policies and practices impact the mental health of children and their families. Crucially, it aims to increase understanding of what can be done to help schools develop a better understanding of students’ behaviour and to support mental health and wellbeing.

What does the evidence say?

The report gathered direct insights from members of the coalition, from children and young people, parents and carers, and academics and professionals though online surveys and virtual evidence sessions.

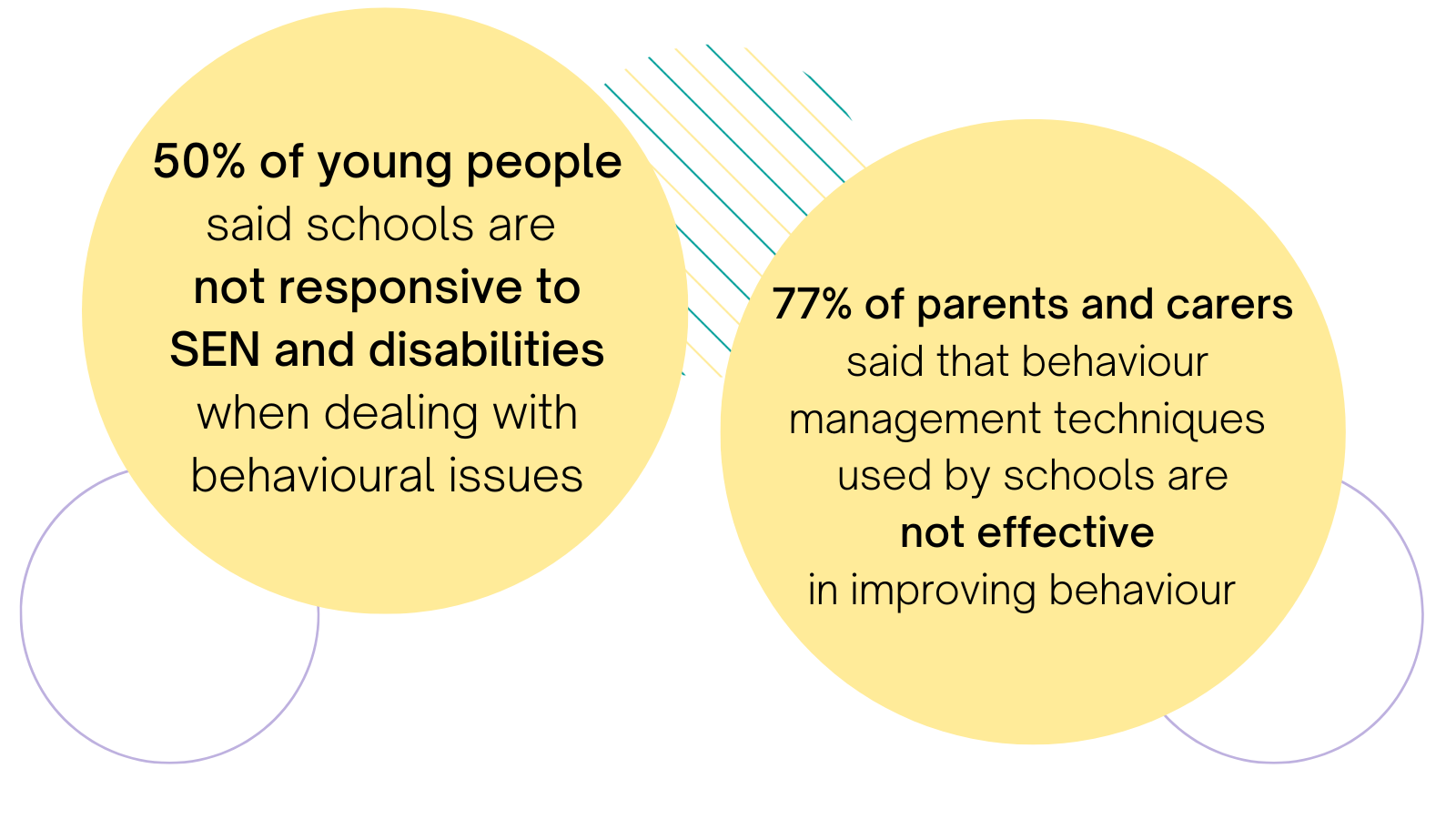

The evidence consistently highlighted that behaviour is often driven by children’s unmet needs, including mental health needs and special educational needs and disabilities. The situation is then exacerbated by schools’ behaviour management techniques, such as removal rooms and exclusions. These are regarded as some of the most damaging techniques. When asked about the impact of these methods on their mental health, young people described feeling worthless and invisible, and reported increased feelings of anxiety.

Young people described feeling worthless and invisible

When asked about the impact of these methods on their mental health, young people described feeling worthless and invisible, and reported increased feelings of anxiety.

First-hand experience

My husband, Mark, works in an outdoor learning setting with children who have often been excluded from mainstream schools owing to problems with their behaviour. Being met in a different environment by a skilled team who have time to listen to them, can completely change their behaviour and enable them to engage in socialising and learning. One boy, for example, whose main coping mechanism was to climb onto a roof or up a tree (the fight flight response), now feels able to talk to Mark and others, and to join in some activities.

Mark would echo one of the key conclusions of the report – that we need to move beyond a place where behaviour is seen as problematic, to a much more concerned and curious place, asking what the behaviour could be telling us.

By doing that, we can identify each child’s needs at a much earlier stage. We’re not saying that schools should tolerate bad behaviour, but they need to find what drives it and avoid punitive behaviour management techniques.

Involving the whole school community

We’re not saying that schools should tolerate bad behaviour, but they need to find what drives it.

The Charlie Waller Trust has always championed a whole school approach, and that view is endorsed in the report’s recommendations. It benefits everyone, staff, pupils, and parents and carers – who often feel blamed and unsupported themselves.

Staff wellbeing is crucial – we know their job is not easy. The Trust provides evidence-based advice, training and support around mental health and wellbeing for staff, parents and the wider school community.

Schools should not be on their own in this. There has to be a properly resourced system of services at a national and local level, so that families can access support for their mental health. Changing the approach to behaviour in school, however, is an important first step and will help to build a more inclusive education system.

Related

Popular

Upcoming event

Join us for the Bath Half Marathon to support young people and their mental health!

The Charlie Waller Trust

The Charlie Waller Trust is a registered charity in England and Wales 1109984. A company limited by guarantee. Registered company in England and Wales 5447902. Registered address: The Charlie Waller Trust, First Floor, 23 Kingfisher Court, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5SJ.

Copyright © 2025 The Charlie Waller Trust. All rights reserved.