Mental Health Resources

Filter resources

Media Types

Topics

User Types

Asking for help (for adults)

Asking for help is a brave step. This guide offers actionable advice on how to ask for help and organisations that can offer support.

Asking for help (for young people)

Asking for help is a brave step. This guide offers actionable advice on how to ask for help and organisations that can offer support.

Building resilience in young people

Information and resources on the key themes around building resilience; sleep, movement, friendship, and self-compassion.

Coping with self harm

A guide for parents and carers on how to cope when your child is self-harming. Find out how to spot the signs and what you can do to help.

Coping with self harm (Welsh)

This guide offers information on the nature and causes of self-harm and how to support a young person for parents and carers in Welsh.

CoRAY mental health lesson plans

Our mental health lesson plans and resources are designed to help teachers and anyone who works with children and young people, and also by parents and carers have conversations about mental health topics.

CoRAY resources for parents and carers

Our mental health lesson plans and resources can be used by parents and carers to have conversations about mental health topics.

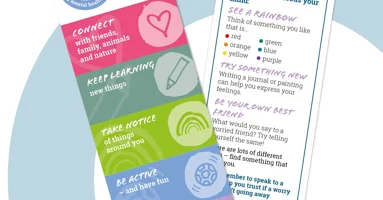

Five ways to wellbeing bookmark

Our colourful five ways to wellbeing bookmark is based on the 'Five Ways to Wellbeing' principle (NHS). It includes practical techniques to help you distract from worries and calm you mind.

Five ways to wellbeing bookmark for children

Our colourful five ways to wellbeing bookmark for children is based on the 'Five Ways to Wellbeing' principle (NHS). It includes helpful techniques for when children are feeling worried.

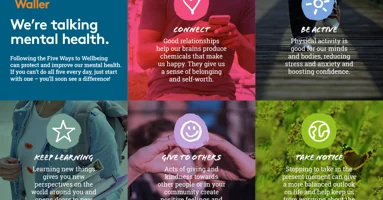

Five ways to wellbeing posters

Seven page poster pack - one for each of the Five Ways to Wellbeing plus two all-in-one designs.

In our own words

This is a package of resources for parents, carers, teachers, and others who want to support the mental health of children and young people.

Life at university poster

This A4 poster features a handy QR code directing students to a Charlie Waller page with guidance to support them through many common obstacles.

Life at university postcards

Support student mental health with these A6 postcards featuring a QR code linking to valuable guidance.

Making the move to university: care leavers

This guide is for care leavers going to university, it looks at how you can best access support and offers guidance on how to look after your mental health.

Making the move to university: international students

This resource covers everything you need to know about looking after your mental health if you're moving to another country for university.

Making the move to university: LGBTQIA+ students

This resource covers everything you need to know about looking after your mental health if you're moving to another country for university.

Making the move to university: not fitting in

This resource helps students or groups of students who feel as if they don’t fit in, by offering guidance on how to stay mentally healthy.

Making the move to university: Students with adverse childhood experiences

This guide is for young people who have had adverse childhood experiences, and offers support on how to look after your mental health when going to uni.

Making the move to university: young carers

This guide is for young carers and offers support on how to look after your mental health when going to uni as well as how you can best access support.

Managing stress and anxiety

This resource offers guidance on how to manage your time and stress levels ahead of exams or assessments, and strategies to help you keep yourself mentally well.

Managing stress and anxiety poster

This A4 poster offers the following six practical tips and pieces of advice on how students and apprentices can manage stress and prevent burn out.

Managing your mental health during exams

This guide offers some simple tips and reminders of how to take care of yourself when exam season approaches, and how to reach out for help and support if things get too much.

Perfectionism

This guide explains what perfectionism is, how it can be both healthy and unhealthy, and the impact it can have on wellbeing. It looks at ‘unhealthy perfectionism’ – how to spot it and advice on how to develop effective interventions.

Recognising and responding to self-harm in schools

These resources include training and information to help school staff recognise and respond to young people who self-harm. It is aimed at all staff working in schools, including those in admin, support and teaching roles.

Results and clearing

The wait until results day often brings mixed emotions. Many students go through the clearing process. This guide will help you understand what to expect, how to adjust to changes, and maintain good mental health.

Schools' mental health policy template

A practical toolkit designed to help staff to develop a mental health policy for schools.

Self harm: stories from parents and carers

Our video and advice provides guidance for parents and carers of young people who are self-harming and steps that you can take to help them.

Self harm: stories from those who work with young people

Our video and advice provides guidance for people who work with young people on steps that you can take to help them if they are self-harming.

Self harm: stories from young people

Our video and advice provides information for young people who are self-harming on understanding self-harm and where to get support.

Starting university: a guide for students

University can be fun and exciting but it can also be exhausting and challenging mentally. Take a look at our range of guidance about starting university and looking after your mental health.

Stepping forward

‘Stepping forward‘ is a unique stop-motion animation film about the transition between primary school and secondary school.

Supporting a child with anxiety

This guide provides parents and carers with helpful tips and strategies on how to support a child with anxiety.

Supporting a child with depression

This guide provides parents and carers with tips to help better support their child with depression.

Supporting a child with an eating problem

This guide provides parents and carers with helpful tips and strategies on how to support a child with an eating disorder or problem.

Supporting school transitions

Tips for parents and carers whose children are starting secondary school. They were provided by parents and carers with lived experience of supporting young people struggling with their mental health.

Supporting students’ mental health videos

These animations offer practical tips on how personal tutors and other academics can make a positive difference to students’ mental wellbeing.

Supporting your child with exam stress

This guide is designed to support parents and carers in helping their children manage exam stress and maintain good mental wellbeing. It provides practical advice on how to create a balanced approach to studying, recognise signs of anxiety, and offer encouragement.

Supporting your students with exam stress

This guide is designed to help educators support their students' mental health and wellbeing during exam periods. It offers practical advice on creating a nurturing school environment, recognising signs of anxiety, and promoting resilience.

Talking about suicide for college staff

This resource equips staff with the knowledge to respond effectively and support students at risk of suicide and self harm. The guide builds confidence in addressing mental health concerns and creating a safe campus environment.

Talking about suicide for university staff

This guide helps university staff have a better understanding of suicide and self-harm. It aims to better equip them to respond and support someone who they are concerned may be at risk of suicide.

University mental health policy template

An evidence-informed toolkit for HE providers, giving guidance on creating an effective mental health and wellbeing strategy, as part of a whole institution approach.

Wellbeing Action Plan for Adults

Our Wellbeing Action Plan for Adults is designed to help you reflect on your emotional needs, how to look after yourself and where to seek help if you ever need it.

Wellbeing Action Plan for Children

Our Wellbeing Action Plan for children helps children identify their own challenges and what helps them. Designed for teachers of Key Stage 2 and 3, and to be personalised to enable children to build their own wellbeing toolkit.

Wellbeing Action Plan for Young People

Our Wellbeing Action Plan for young people is ideal for students attending sixth form or college, whether or not they have experienced mental health issues.It's a practical tool that helps students think about how to look after their mental health, when they may need support and where to seek help.

Young people who self-harm

Developed by researchers at the University of Oxford, this guide includes information on the nature and causes of self-harm and how to support a young person who is self harming for school staff.